Situational Analysis: A Phased Approach

Drawing from knowledge from experience, desk review and organizational inquiry (document review and key informant discussions) are critical to ensure that analysis builds from CARE’s and others’ diverse sources of learning within the country context.

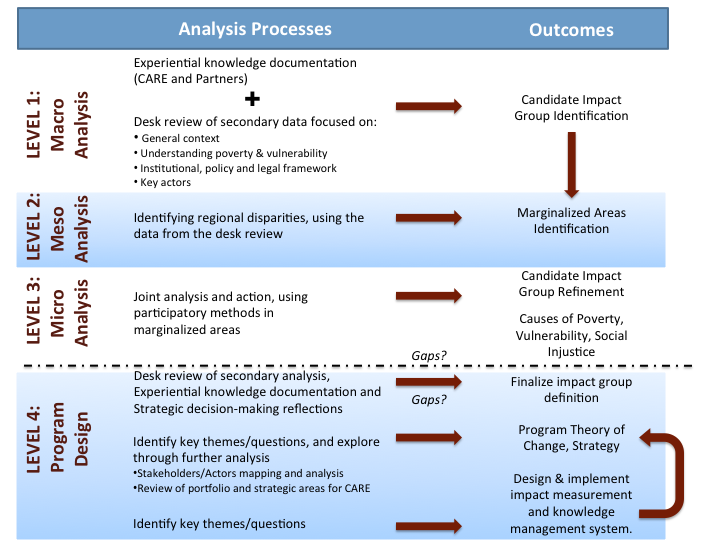

As the diagram below illustrates:

- 1st phase - Macro Analysis: a literature review combines with CARE staffs’ and partners’ knowledge from experience to produce a candidate set of impact groups. If quality, availability, and disaggregation of existing data is insufficient, teams may also seek further information from key informants.

- 2nd phase - Meso Analysis: using the same data, a spatial analysis of the data is done to identify regional disparities, which help reveal where the poorest and most marginalized populations are located and the drivers for marginalization. This will generate a set of candidate impact groups combined with an identification of the most marginalized areas. This is intended to help you choose a locality for your micro-level analysis.

- 3rd phase - Micro Analysis: almost exclusively primary data collection, the Country Office will be able to finalize the selection of impact groups and refine their definition.

Phases 4 and 5 are discussed below:

Definitions

In sociological research, macro refers to the largest social grouping, at the level of the society as a whole. At this level (national or broader), institutions that affect the masses are relevant here – the economy, government, the norms of the society – and, for our purposes, the environmental phenomena affecting the whole population as well.

The meso level pertains to the smaller social groupings or smaller systems of people who follow a set of guidelines. These reveal to us the divisions in society and thus the social and economic inequities across a country context. These may also manifest spatially. Here, regional or sub-national institutions are relevant.

The micro level breaks down to a smaller scale geographically and socially. For our purposes, the critical unit of analysis is explanatory of the unequal power relations that account for the marginalization of a grouping of people. At smaller levels of analysis, micro extends to the household and the individual.

How Much Analysis is Enough to Move Forward in Program Design?

A common question raised across country offices is how much analysis is adequate to start developing the program theory of change and strategy.

No single situational analysis will be able to answer all questions, but it should offer the team a level of confidence in the choice of impact groups, even when data gaps still exist. For this reason, there is a 4th phase on the diagram that corresponds to a critical reflection moment, after the findings of the micro-level analysis are available. Here it is important to pause and reflect on two important questions:

- How adequate is the information?

- Which findings require deeper exploration before selecting final impact groups?

The diagram shows a 5th phase. Here, one switches from design to development of the programs that involves constructing the theories of change. An iterative process of going back and forth between the analysis and the program theories of change occurs here, as the team seeks to refine the theories of change.

It is important the team not be stymied by information gaps but agrees that some answers can be gotten through the measurement and learning system for the program. Indeed, as previously mentioned, analysis is an integral part of all phases of the program cycle, as explained further below.

Preparing and Planning Analysis

Situation analysis requires careful preparations and realistic planning on who to involve, resources available, team capacities, time, ethics and research design (selection of methods and respondents).

Who to Involve

In situational analysis, partners play an important collaborative role. That means, at a minimum, teams should carry out a survey of key actors very early on to identify existing or new partners with whom to engage in analysis.

To support this process, consultants may offer important support in facilitating situational analysis and building staff capacity in critical inquiry. However, staff should remain involved and invested in each dimension of analysis to ensure ownership over the process, findings and program as well as to build internal capacity for analysis.

Considerations in Design

- Resources for analysis: Time available, project/program budget, as well as human resource availability (CARE TA, experience in research, partnerships)

- Ethics (see the Ethics page): risks posed in people’s participation in analysis and alignment with Do No Harm:

- What may be potential risks to participants or community members linked to this study and how do we ensure we are conflict sensitive?

- How can we ensure that the analysis process is not just “extractive” but is accountable to communities, and promotes empowerment and learning?

- How can we ensure that we work sensitively and respectfully within communities?

- Training and Supporting Teams (see the Training page): Gender equity and diversity sensitivity, conflict sensitivity, facilitation skills. research and analysis skills among staff and partners.

- Confronting Researcher Bias: A feedback mechanism to guard against researcher bias, whether internal or external.

- Engaging Mixed Methods: Mixed methods and diverse respondents for a robust foundation of information for analysis.

- Organizing the Research (see the Planning and Design page): Someone must oversee the schedule for completing the situational analysis, fitting it with Country Office needs for initiating programs and applying for donor funds; agreement on the sequencing and the spacing of the research; some non-negotiable deadlines that derive from or are aligned with the Country Office’s strategic and annual operating planning.

- Timing of Field Research: Take into account the valuable time and schedules of community members whom we would like to involve in analysis - seasonal climate, administrative and political calendars (elections, planning/budgeting/reporting cycles) alignment with planned events within ongoing projects (mid-term reports, baselines, evaluations, etc.).

Pages In this Section Include:

Overview of the phases of analysis for program design

Macro Analysis Guidance, including frameworks for macro analysis on:

Meso Analysis Guidance: on looking across the macro-level analyses to gain an understanding of regional pockets and dynamics of inequality, poverty and exclusion.

Micro Analysis Guidance: on participatory methods that build from macro and meso analyses to paint a picture of local level characteristics and dynamics.

Components of Situational Analysis

Situational analysis involves looking across a number of important dimensions on multiple levels (from international, national, regional, local, household and interpersonal). Given the vast amount of information in each of these categories, Country Office teams must prioritize what they are looking for:

- What are the key research questions you need to answer?

- How could answers to those questions help get to where you want to go?

- How can it help you identify impact groups, understand the issues they face, what drives their poverty and what opportunities exist to positively influence change in their lives?

Follow the links below for an overview of the different levels and thematic areas of situation analysis, and how these different types of analysis are important.

- Macro Analysis Guidance

- Meso Analysis Guidance

- Micro Analysis Guidance

<< Back to Analysis and Program Approach Introduction <<

Note: On Situational Analysis

Across each level and area of analysis, Country Office teams must consider who are the key actors or groups whose actions, incentives and interests have an impact on the situation; what is the source and degree of their influence; and what are their relationships with one another.

For this reason, stakeholder analysis represents a critical component in any program design. For more information, please visit the Stakeholder Analysis Page.